Key ideas

Even without the malaise of living through a pandemic, fortifying our resilience to adversity always has value.

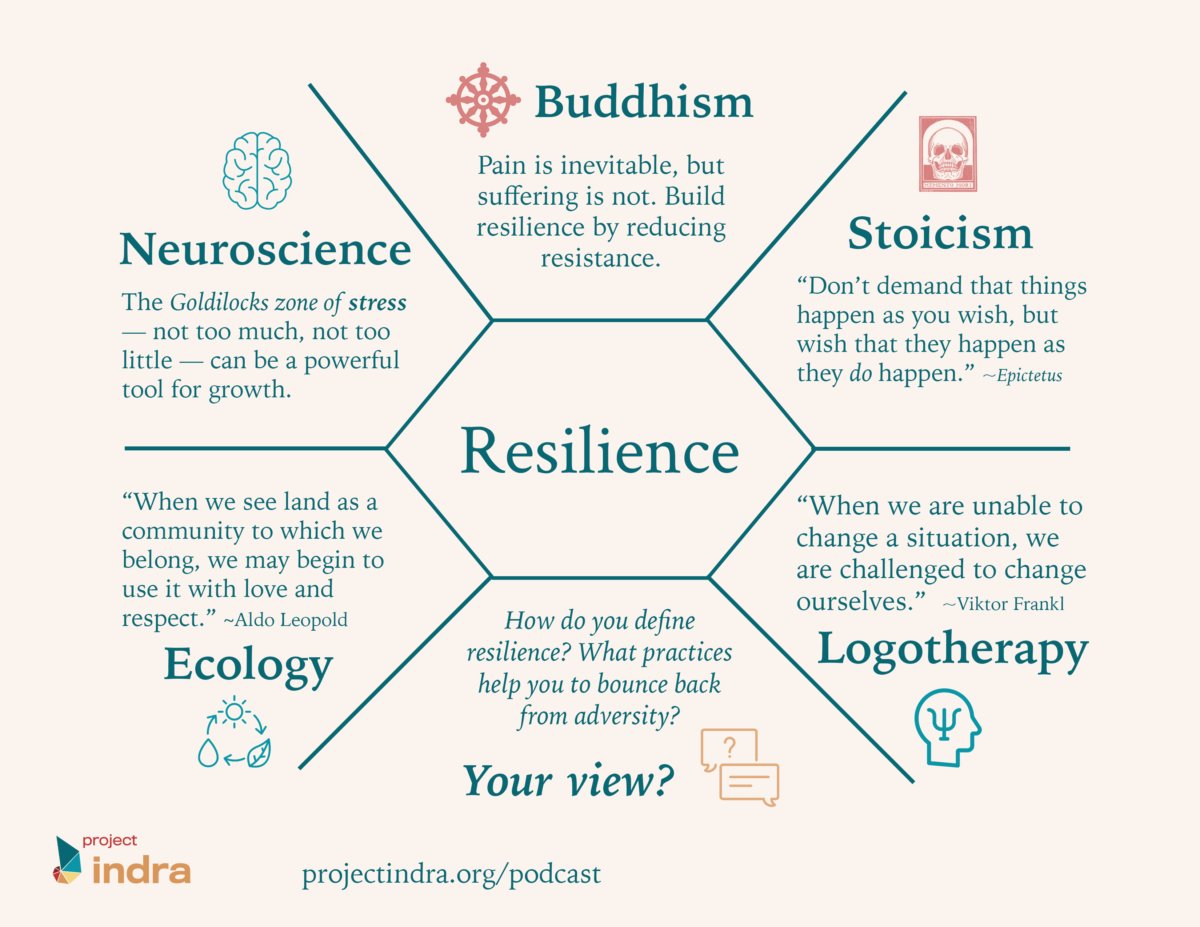

- Buddhism: Pain is inevitable, but suffering is not. Build resilience by reducing resistance.

- Stoicism: “Don’t demand that things happen as you wish, but wish that they happen as they do happen.” ~Epictetus

- Logotherapy: “When we are unable to change a situation, we are challenged to change ourselves.” ~Viktor Frankl

- Neuroscience: The Goldilocks zone of stress — not too much, not too little — can be a powerful tool for growth.

- Ecology: “When we see land as a community to which we belong, we may begin to use it with love and respect.” ~Aldo Leopold

Transcript

The past year and a half have been challenging for pretty much all of humanity. No doubt each of us has faced some form of setback, loss, anxiety, or even just plain discomfort in these times of Covid. With these difficulties in mind, I set out to explore some insights from various traditions on how to build resilience. Even without the malaise of living through a pandemic, fortifying our resilience to adversity always has value. This episode wraps up a series looking at the concept of resilience from five different perspectives, including Buddhism, Stoicism, Logotherapy, Neuroscience, and Ecology.

I’ve learned a lot from this exploration. I hope that some of these insights can help you as well.

From Buddhism, I found the idea of the “second arrow of suffering” to be helpful. Suffering arises when we resist painful, difficult, or otherwise undesirable circumstances. This resistance is the second arrow of suffering, which saps our energy. Our resistance distracts us from taking the actions that would help us overcome the difficult situation. Instead, we can bring awareness to our thoughts and emotions as suffering arises. Doing so can help calm the mind, reducing the control our repetitive and unhelpful thoughts exert on our minds. As a result, we regain a sense of agency. We increase our capacity to take helpful actions.

From Stoicism, the idea of Amor fati struck me as a valuable mindset for resilience. Life will often be challenging, uncomfortable, or painful. We will experience losses and setbacks. But we don’t have to consider all of these experiences as negative. In fact, in many cases, we might even come to find great value in hardship. The Stoic idea of Amor fati encourages just that: to love one’s fate, regardless of what fate might have in store. Like the Buddhist approach, we shift our mindset from one of resistance to acceptance. But Amor fati even goes a step further, welcoming and embracing our circumstances, whatever they are. By doing so, we can tap into tremendous inner strength. We can use setbacks like fire forges tools. An “untroubled life,” as Seneca describes, does not produce great humans who do great things.

Fast-forwarding nearly 2000 years, Viktor Frankl echoes this insight from Seneca. From Frankl and the branch of psychology he founded called Logotherapy, we see a compelling case for the influence of meaning in our lives — even in suffering. His chronicles of life in Nazi concentration camps depicted herculean resilience in the face of horrific pain and adversity. However, this resilience doesn’t always come from physical strength but from our sense of purpose: our ability to find meaning in the circumstances that life presents us. As he describes, we need “... not a tensionless state but rather the striving and struggling for some goal worthy of [ourselves]. What [we] need is not the discharge of tension at any cost, but the call of a potential meaning waiting to be fulfilled by [us].”

But, as I learned from a brief exploration of the neuroscience of resilience, we all have our limits. Our life experiences can sometimes inhibit our capacity to overcome adversity. “Toxic stress” negatively affects our resilience, causing mental and emotional trauma over time. Toxic stress takes many forms, including abuse, violence, poverty, or other chronic stressors. In contrast, the “right” kind of stress under the right conditions can help cultivate personal growth as we adapt to a new level of challenge. This “helpful” stress is called eustress. Our brains can adapt because they are plastic. Or in other words, they will change throughout our lives due to the conditions we experience. This idea of neuroplasticity means that we’re never truly stuck. With the proper support, training, and mindset, we can cultivate a greater capacity to respond to stress. Like Viktor Frankl’s Logotherapy proposes, recent research indicates that having a sense of purpose and clear values can fortify our resilience.

Finally, I looked at resilience from the perspective of ecology. We are not isolated beings; we are part of a deeply connected system. Our well-being depends on the well-being of the natural world that sustains us. But like us, nature has its limits. When subjected to intense or persistent disturbances, ecosystems can fail. I can see a parallel between the effects of toxic stress on people with these kinds of impacts on nature. Ecological resilience refers to an ecosystem’s capacity to bounce back from these disturbances, like fires, floods, deforestation, pollution, or other impacts. When ecosystems fail, they can no longer provide the kinds of ecosystem services our societies need to survive, such as clean air and water, fertile soils for agriculture, and other critical resources. It is, of course, in our best interest to support the resilience of these ecosystems we depend on. One straightforward way to do this is to protect biodiversity. Greater diversity within ecosystems fosters greater ecological resilience.

I’ve only scratched the surface of each of these traditions, systems, and perspectives. No doubt, there are many other views we could explore to learn even more about resilience. One thing that is clear from this study, though: with every layer uncovered, countless more layers are waiting below. We could spend a lifetime studying any one of these traditions, and probably at the end, there’s still more to learn. More perspectives to consider.

Which points to the theme I’d like to explore in the next series: complexity. We live in a world of such vast, incomprehensible complexity. And it’s only getting more complex by the day. All of our programs, decisions, and actions are affected by interactions that often defy understanding. Solving any of our social, environmental, or economic problems requires an embrace of this complexity.

Subscribe to this podcast for more insights on the best of what great minds have learned through the centuries to help us with these big problems. And please share this with a friend if you think it would be helpful to someone. Until the next time, be well!

Podcast soundtrack credit:

Our Story Begins Kevin MacLeod (incompetech.com)

Licensed under Creative Commons: By Attribution 3.0 License

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/